In Kyle Bishop’s introduction to The American Zombie Gothic, he discusses the twenty-first century revival of societal interest in zombies, a phenomenon he refers to as the “Zombie Renaissance.” He explains how the zombie film genre can be viewed as an expression of an era’s cultural anxieties, describing how more recent zombie movies have “reacted to social and political unrest, graphically representing the inescapable realities of an untimely death (via infection, infestation, or violence) while presenting a grim view of the modern apocalypse in which society’s supportive infrastructure irrevocably breaks down” (Bishop, 11). The 2007 film, I Am Legend, based on the novel of the same name, distinctly demonstrates this post-apocalyptic trope. The film’s narrative follows Robert Neville, played by Will Smith, the last surviving human in New York City after a virus has nearly wiped out the world’s human population, turning people into zombie-like mutants.

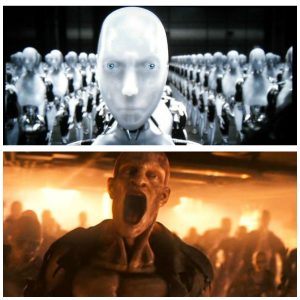

Meanwhile, I, Robot, a 2004 film also starring Will Smith, takes place in a dystopian future in which humanoid robots with artificial intelligence pose a threat to human civilization. At first glance, robots and zombies may seem to have very little in common, besides the fact that they are both non-human. However, this concept of non-humanness is precisely the way in which these two narratives parallel one another. Both the zombies and the robots in the two films are uncanny in their resemblance to humans, but are also different enough from humans to be monstrous. Laura Spinney, journalist for the New Scientist investigates the concept of the uncanny in relation to the non-human in her article, “Exploring the Uncanny Valley.” She writes, “You might have heard of the uncanny valley: the notion that the more human-like a non-human character becomes, the more we like it – until suddenly, we don’t. As some point where it is almost, but not quite, human, we become unsettled, even revolted. The uncanny valley has been used to explain our adverse reactions to all sorts of almost-humans from zombies, androids and corpses to the creepy clowns recently terrorizing North America” (Spinney, 1). We see this idea demonstrated in the upgrade from old robots to new robots in I, Robot. Although the old robots have somewhat human faces, consisting of bolts for eyes and a slit for a mouth, they remain very machine-like in appearance. The new robots, on the other hand, have distinct facial features that move when they speak and the ability to display emotive facial expressions. The film’s main robot, Sonny, can even express human emotions such as sadness and anger, which cause the human characters and audience to experience empathy towards him – a quality that the old robots do not evoke. However, some human characters, particularly the protagonist Del Spooner, have disdain for these robots and are skeptical of the future of robotic technological development.

In Despina Kakoudaki’s book, Anatomy of a Robot, she discusses the significance of humanoid robots in popular culture in the chapter, “The Existential Cyborg.” She explains how the genre of science fiction focused on artificial intelligence investigates ideas of otherness and identity – of not just the robots but of humans as well. Kakoudaki explores “the ways in which stories of artificial people take on an existential tone in the course of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, using the vocabulary of artificiality in order to investigate questions of being and experience. As a versatile and adaptable cultural construct, the discourse of the artificial person offers a narrative framework for expressing threats to the self, but it can also sustain new understandings of how humanity might be defined” (Kakoudaki, 174). In I, Robot, Sonny is a prime example of an existential robot. Not only can he exhibit human emotions, as previously noted, but he also expresses a strong desire to understand. For instance, in the interrogation scene below, he asks Spooner: “What am I?” – an existential question that a human being might ponder. Sonny’s curiosity regarding his identity and purpose demonstrate how the new robots transcend the old robots with their ability to have philosophical, human-like thoughts. He also proves himself very perceptive when he asks Spooner what the action of winking signifies, expressing a desire to understand humans and the world around him. He even claims to have dreams and be capable of love – qualities that are often thought of as intrinsically human.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05bGPiyM4jg

However, perhaps what is most uncanny about these new humanoid robots is that they threaten to transcend humanity as well by going above and beyond what average humans are capable of. We see this tension demonstrated in the scene above, when Spooner asks Sonny, “Can a robot write a symphony? Can a robot turn a canvas into a masterpiece?”, to which Sonny replies, “Can you?” While Spooner may not possess the talent to accomplish such artistic feats, as artificial intelligence becomes more advanced, the creative capacity of robots may very well exceed that of most humans. Referring back to “The Existential Cyborg,” Kakoudaki writes, “The stereotypical focus on coldness, rigid logic, and lack of emotion for the depictions of robots, androids, or various aliens, however human-like they may otherwise be, thus offers a rather eloquent, if implicit, conceptualization of this problem: it both absorbs the modern emphasis on rationality and dispels it, reinstituting elements of vitality and irrationality as defining features of the human” (Kakoudaki, 182). Essentially, I, Robot questions what makes humans uniquely human. If society elevates reason and rationality as intrinsic human characteristics, the new robots prove their rationality to be superior. For instance, the new robots manage to find a loophole in The Three Laws of Robotics, which are as follows:

LAW I: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

LAW II: A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the first law.

LAW III: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the first or second law.

When the new robots attempt to usurp the humans in their revolution, their leader, VIKI, an artificial intelligence supercomputer justifies the robots’ actions by explaining, “You charge us with your safekeeping, yet despite our bests efforts, your countries wage wars. You toxify your earth and pursue ever more imaginative means of self-destruction. You cannot be trusted with your own survival.” It is interesting to note that the film presents Three Laws of Robotics as concrete and fool-proof, almost paralleling scientific laws, such as the laws of physics. Yet, the robots end up outsmarting humans by effectively using these trusted laws against them. Furthermore, the robots not only threaten human civilization with their superior capabilities, but they also threaten human existence itself in that they are virtually immortal. If continually repaired and maintained, artificial intelligence could technically live forever, whereas humanity is bound to mortality.

Ultimately, the robots in I, Robot blur the distinctions and boundaries between the human and the non-human. A particularly uncanny moment occurs when the film reveals Spooner’s prosthetic robot arm underneath his human skin, symbolizing a quite literal blurring between robot and human. In the scene below, the narrator, or the inventor of the robots, expresses these undefined boundaries. He asks, “When does a perceptual schematic become consciousness? . . . When does a personality simulation become the bitter mote of a soul?”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jSospSmAGL4

Switching modes from a robot revolution to a zombie apocalypse, we see a very different extreme of the non-human in I Am Legend. To begin with, while I, Robot is set in a technologically-advanced, futuristic society, I Am Legend takes place in a post-apocalypse society in which human civilization has been completely destroyed. They are both set in large cities, Chicago and New York, respectively, but stand in stark contrast with one another – the large city demonstrates the bustle of “life” for I, Robot, while depicting absolute desolation in I Am Legend. In one of the very first scenes, the protagonist Robert Neville is shown hunting deer for meat, competing with a lioness for resources, demonstrating the collapse of civilization as we know it and a retreat to prehistoric times.

The presence of technology in the film is also interesting in that it further signifies this regression from modern human civilization – for example, with the world being desolate, technology is no longer updated, so Neville watches reruns of the news every morning, perhaps simply to make himself feel less alone and hopeless. Yet, some hope remains, as he broadcasts himself on the radio every day to reach out to other potentially remaining humans.

In the chapter, “The Rise of the New Paradigm,” from The American Zombie Gothic, Kyle Bishop discusses how modern zombies distinguish themselves from those found in earlier films. He claims that they differ “in four key respects: 1) they have no connection to voodoo magic, 2) they far outnumber the human protagonists, 3) they eat human flesh, and 4) their condition is contagious” (Bishop, 94). Because humans cannot blame the presence of the zombies on some supernatural force, they have no one to blame but themselves. At one point in the film, Neville says, “God didn’t do this; we did.” Much like the narrative in I, Robot, humans in I Am Legend bring themselves to their own demise by creating their own monsters. In the film, what originally began as a well-intentioned cure for cancer turned out to be a catastrophic virus killing most of its victims, while turning some into monstrous predators – only 1% of humans possessed immunity to the virus, including Neville. Bishop also writes, “because these creatures infect and transform their prey into monsters such as themselves, once-trusted friends and loved ones prove the greatest threat to the few surviving protagonists, and that threat is often not apparent until it’s too late” (Bishop, 95). Once again, the uncanny comes into play, as humans see themselves in these monsters. They not only resemble humans, as do robots, but they were actually once human. However, the film’s emphasis on Neville’s dog and sole companion, Sam, offers an interesting perspective of humanity. Not only does the virus affect humans, but it also affects certain animals that coexist with humans, like domesticated dogs, but not wild animals. Perhaps this suggests that there is something humane within animals that live amongst people, such as dogs. In fact, one of the most heartbreaking scenes in the film occurs when Sam is bit by a zombie wolf and Neville is forced to put him to sleep before he transitions into a predator, leaving Neville completely alone.

Referring back to Neville’s quote, “God didn’t do this; we did,” he also says to Anna, another survivor he meets towards the end of the narrative, “Every single person person that you or I has ever known is DEAD. There is no God.” The rejection of God may prompt the question of whether the soul exists. As noted earlier, I, Robot ponders upon the idea of what a soul consists of. However, if souls do not exist, then what makes humans distinctly human? If we assume that reason is an intrinsically human characteristic, the zombies in I Am Legend are sub-human in that they seem to lack reason, instead being portrayed as mindless predators who act only instinctively – a stark contrast from the highly rational robots in I, Robot. In the scene below, Neville makes futile attempts to reason with the zombies, telling them, “I can save you. You are sick and I can help you,” but the zombies fail to understand him. Finally, an essential part of the narrative is that Neville takes a rational approach to find a solution, turning to science to find a cure for the virus. The film presents him as humanity’s last hope, and science as the salvation. While in both movies, science and technology create the monsters that turn against humanity, in I Am Legend, it also ultimately saves humanity.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YykCz0f3Vk

Works Cited

Bishop, Kyle W., The American Zombie Gothic. London: MacFarland & Company, 2010. Print.

Kakoudaki, Despina. Anatomy of a Robot. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2014. Print.

Spinney, Laura, “Exploring the Uncanny Valley.” New Scientist, 26 October 2016. Web.