I was intrigued by how many of my classmates wrote on similar topics, even though we played different games. I noticed a multitude of themes, but I’m going to focus on three: player choice, the difference between casual and hardcore games, and broader significance.

I’m defining player choice as the ability of a player to do/be whatever they want within a game. I looked at this when addressing Dragon Age: Origins and how it failed to be an open-world by limiting where a player could explore. Luke found a very similar experience in Pokemon X, where certain pathways are blocked to a player until they complete other quests. Paul addressed it in regards to Bioshock, and how the player think they’re making independent decisions, but it comes to be revealed they’ve just been following commands the whole time. Bioshock thus draws attention to to the fact the player lack choice. This is similar to Alec’s point about Dragon Quest V, where player’s must occupy a male character, and the only choice they get is the character’s name. I feel like this came up because games are so often marketed as stories that you get to experience in whatever way you want, but most actually require players to follow a specific path to completion.

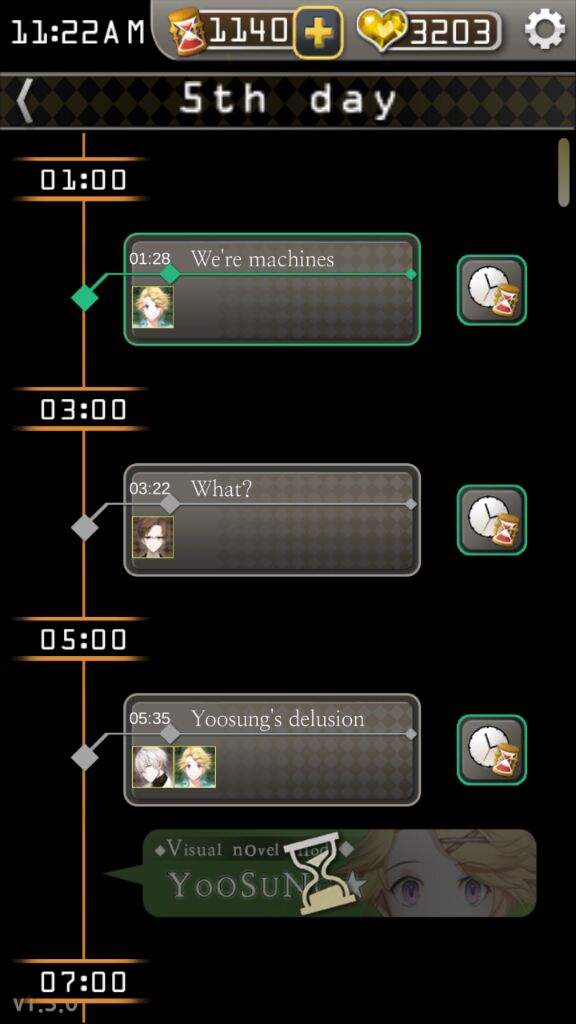

So often we believe that there’s a strict line between casual and hardcore games, but I think we discovered that those distinctions aren’t as clear cut as we believed. I wrote about how Mystic Messenger was still casual even if parts of it seemed hardcore, using “A Casual Revolution” by Jesper Juul. Ryan did a similar analysis with the article, looking Super Smash Bro’s. He pointed out that game didn’t fit cleanly into casual or hardcore. The article came up again in Luke’s analysis of Pokemon X, which also doesn’t fit neatly into either category as it makes use of elements from both.

The last category was how a lot of people drew in external sources, by relating games to their broader significance in the word. Luke talked about how psychological studies around conservation use Pokemon to make their argument. He pointed out though that those studies missed certain elements because they likely hadn’t played the game, showing the misconceptions about gaming in the world. Paul did something similar in his analysis of Bioshock talking about the cultural significance of its science-based narratives. This game was just a recent example of the cultural trend to present fantasy elements grounded in science.

Even though we played a wide variety of games, we still got hung up or interested in similar issues, which I think may show the limits of videogames as they exist now, and places for them to explore in the future.